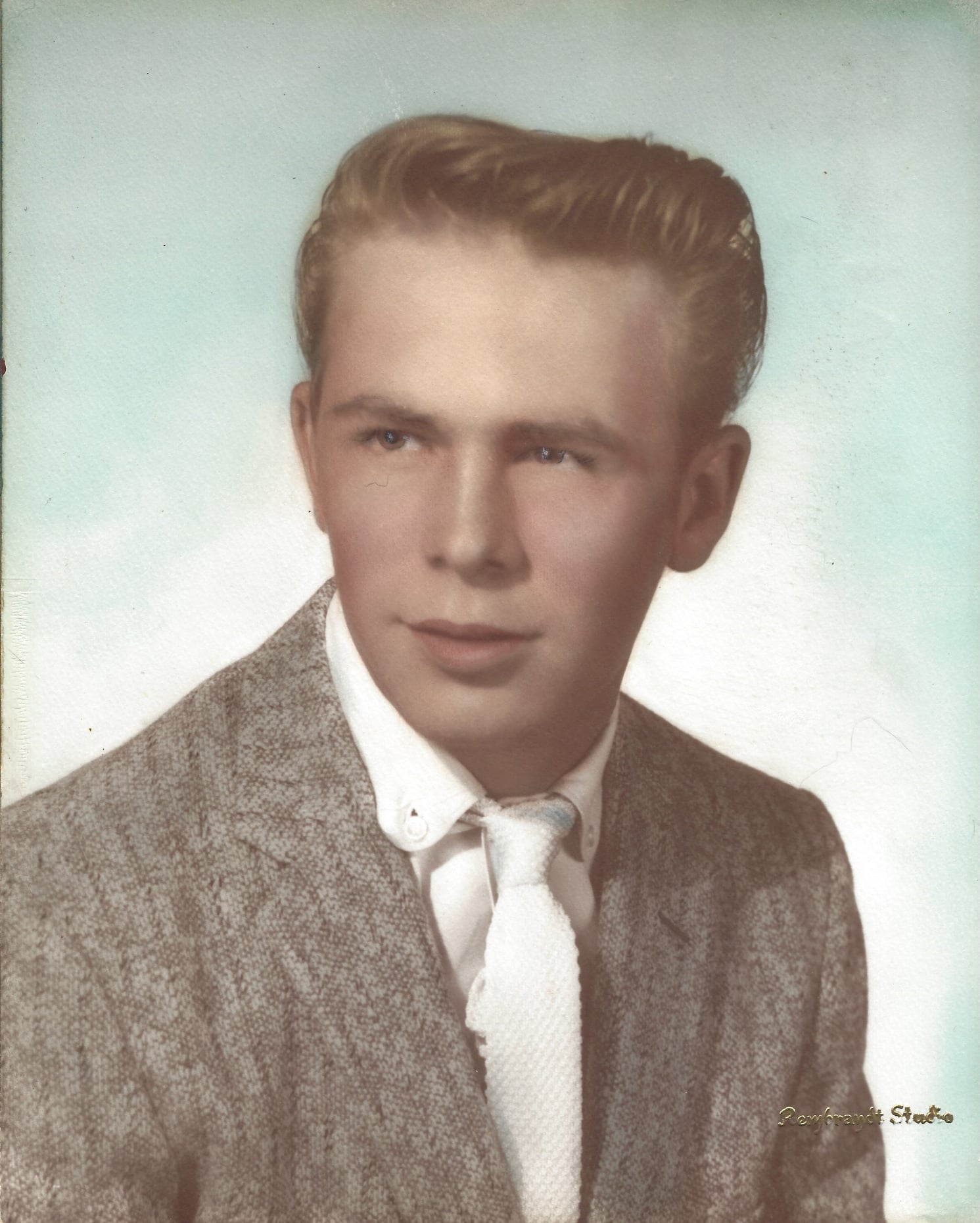

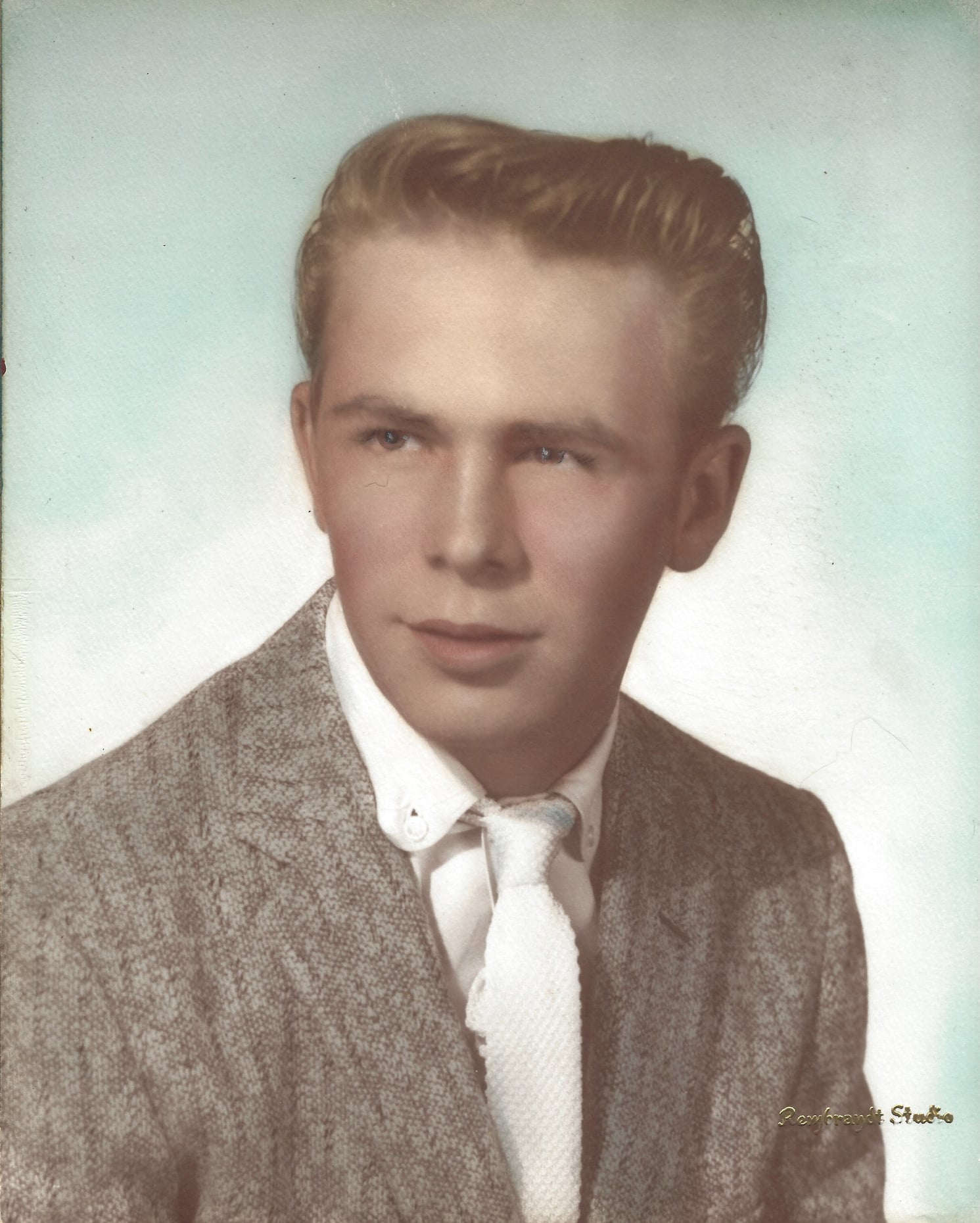

Ronald C. Brockmeier, my father, passed away on January 21, 2020 in Dorchester, Wisconsin. He was 79, and had spent about two and a half years suffering from vascular dementia and memory loss. He was preceded by his wife, Tina, who passed in July 2019.

It’s hard to write anything short of a novel about my father’s passing. How do you compress a life into a few paragraphs or pages? He was many things, and “easy to describe” wasn’t one of them.

Firstly, nobody used his given name, excepting Tina from time to time. I’d hear her over his shoulder while he was on the phone, “Ronald!” Usually when he was saying something inappropriate. This happened often. He was given to saying inappropriate things.

No, most people called him Ron, but for many years most people just called him Rotten. Rotten Ron was his nickname for pinstriping. It was one of many jobs he did over the years, and the one that he did the longest. He was driven to create, he wanted to paint designs and try new things.

So he taught himself how to pinstripe at a young age. The way he told it, someone asked if he could, so he said “yes,” bought the brushes and paint, and did it. And got paid. And kept doing it. Along the way he added sign painting and lettering, and got savvy about what to charge and how to drum up business. Had it not been for the advent of cheap vinyl signs and such in the late 80s, I suspect he’d have kept lettering and pinstriping as a job well into his 70s.

He had other jobs, as well. Or ways to make money, anyway. Before I was born, he hustled pool for money in addition to sign painting and pinstriping. Gambling, he taught me, was work. If there’s money on the table, it’s work, not fun. Nevertheless he enjoyed shooting pool and went back to it later in life, often going to the local bar to shoot pool for money. He usually won, at least to hear him tell it.

At any rate, he wasn’t there to drink. My father wasn’t a big drinker, he enjoyed a beer now and again — oddly, he would put salt in the beer the few times we went out to dinner somewhere that he’d order a beer — but mostly, he was not a drinker.

On the other hand, he smoked pot when I was a kid. A lot of it. Grew it in the basement, too. Loved Cheech & Chong movies, and didn’t seem to see anything wrong with letting me watch them with him as a youngster. I think I first watched Up in Smoke when I was 10 or 11. We had a VCR early on, mainly because he couldn’t abide by movie theater prices.

He was also a bouncer on Laclede’s Landing in St. Louis, well before I was born. The fact that he was skinny and only 5’9” should give a clue as to his overall disposition. The only fair fight, he often told me as I grew up, is the one you win.

Another job was working at an auto factory. He worked at Chrysler in Fenton, Mo. for years, and was working there when I was born in the 70s. He was a staunch supporter of unions, and a lifelong Democrat. He voted. “Both parties want to steal from you,” he’d say, “but at least Democrats believe you have to have something to steal, first.”

My father loathed Reagan. Republican presidents in general, but Reagan in particular. He said more than once, he wanted to meet President Reagan so he could tell him, “I didn’t like your movies, either.”

In the late 70s he started volunteering with the Pacific Fire Department. And then he got a job as a firefighter, and eventually earned his EMT and became a paramedic. There’s no pride like the pride of a son who can say “my dad is a firefighter.” I relished that. I tromped around in his boots and gear at every opportunity.

It never occured to me people died doing it. Maybe it didn’t occur to him either, until it happened to a friend of his. He didn’t talk about it, at least not to me, but I overheard things the way you do when you’re a kid. He must have decided the risk wasn’t worth the steady paycheck and eventually quit that job, too.

We lived in a small house built by my grandfather that was intended for three people. A couple and child. The house had to put up with a lot it wasn’t intended for. In 1977, my brother David was born. In 1982, we were flooded out, and then shortly after that my brother Brad was born. Shawn followed a few years later. It was flooded again in the 90s, a few times. It was sold, the foundation jacked up to raise it above flood waters I suppose, and eventually razed altogether. I guess you really can’t go home again. Not that I necessarily want to, home wasn’t always where I wanted to be.

My parents fought, a lot. Truth be told, my dad never wanted to be a parent. I’ll leave that for another day, but suffice to say that parenting wasn’t what he set out to do with his life. But he worked, kept food on the table, and endured a rocky marriage for nearly 30 years. My mother left him long after I’d left the nest, and he fought for custody of my youngest brothers and lost. He was miserable, but I’m convinced he’d never have left — at least as long as my brothers were minors.

That’s not, by the way, praise. My parents fought and fought and fought. They’d split up once when I was still an only child, no older than five. He was dating another woman, she was dating another man. He asked me if I thought he should get back together with my mother. Of course, being young, I said yes out of loyalty. I secretly hoped he wouldn’t. He did. Sorry, dad.

Shortly after my parents finally split in 1997, he met Tina, and they eventually moved to Wisconsin where he’d spend the rest of his years. He always wanted to live somewhere warm, but that never quite worked out. They married in a civil service on April 1st, though the particular year escapes me. I heard about it after the fact.

My father and I were never close the way that some families are. One thing I learned is that you can’t retrofit a parental relationship by making up lost time. It’s there, or it isn’t. Don’t get me wrong, I love my father. But the storybook father and son relationship just wasn’t us.

Which isn’t to say I don’t have fond memories of my dad. I do, quite a few of them. Once, we watched a squirrel explode together. Well, that wasn’t the intent. We were sitting at the table, facing the picture window in the living room. A squirrel was skittering along the power lines and then it wasn’t. There was a flash, and the power went out. So did the squirrel. It’s not that we found the squirrels sudden and dramatic demise amusing, but the witnessing of it together was something. How often do you see a squirrel explode, anyway?

Another time, we were coming home from a car show in Kansas. And it started raining, on exactly half of the highway. (We were on the other half.) We didn’t do vacations, trips to car shows were as close as we got.

He owned damn little clothing that wasn’t paint stained. Occupational hazard. When he was pin striping or sign painting, he’d often shape the brush with his fingers and then wipe the paint on his pants. His jeans would accumulate layers of paint. To this day I love the smell of turpentine.

My father often promised to take me fishing, but we only went a handful of times. He invited me often after settling in Wisconsin, but we only found the time once, as adults. But as a child I remember being out on the john boat and trolling around the river. We had milk jugs with part of the tops cut off to hold fish, and I had an idea. If the boat was traveling through the water, surely we were passing many fish. I could just hold the jug in the water and catch a fish!

Wouldn’t work, my father told me. Dumb idea. I tried anyway. A few minutes later, thunk. A sun perch was dazed and confused wondering what the hell it was doing in a milk jug. Sadly for me, the perch was too small to keep. Good for the fish, though.

He also worked like hell to convince me that it was OK to stick my hand in a fish’s mouth to pull out the hook. I finally decided that my father wasn’t one to invite any unneeded doctor bills, and steeled myself to pull out the hook of the next fish I caught. I reeled one in, readied myself to pull out the hook when my father yelled “no! Not that one!” It was a gar, with astounding teeth. This was a setback in our relationship.

My father loved The Three Stooges, and Popeye cartoons. Loved the movie, too. In retrospect, he ceded control of the TV more often than I realized as a kid. We watched my shows pretty often, The Hulk, Dukes of Hazard. And we agreed on Mork and Mindy and Greatest American Hero. He loved M*A*S*H and Hogan’s Heroes. (I maintain that it’s weird as hell that a sitcom was set in a POW camp in Germany during WWII.)

Of course he also introduced me to Benny Hill, and Monty Python, and (one of his favorites) Fawlty Towers. They wouldn’t, usually, let me stay up to watch Soap though. But they didn’t police me watching it in my room on my 13” black and white TV. I just had to hold down the laughing so they weren’t reminded I was breaking the rules by staying up to watch it. He didn’t hold with censorship or dumbing things down for kids much.

I remember him telling the local librarian that if I was old enough to read a book, then I was old enough to check it out. I think the book in question was Cujo, by Stephen King. He’d seen to it we had a full encyclopedia set and set of classic literature. It lived in the hall, where I spent many an hour reading about dinosaurs or sharks or space.

It was my father that recommended Deadwood to me, the HBO series that featured foul-mouthed and murderous saloon and brothel owner, Al Swearengen. No doubt my father saw a bit of himself in Swearengen. Had they lived at the same time I don’t doubt he’d have given Swearengen a run for his money.

Rotten Ron could be weirdly wholesome, too. He loved Fraggle Rock, and The Muppets. He loved Looney Tunes cartoons, and equally hated more modern cartoons that were lowbrow and slapdash. The father who didn’t mind me watching Up in Smoke banned The Simpsons for my younger brothers. If consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds, my fathers mind was neither small nor troubled with hobgoblins.

He loved Bob Ross. So much so he went all Bob Ross on our living room wall, painting a landscape directly above the couch. One of the happy accidents that followed was my brother drawing on the walls in the hallway. He had to concede that he’d set a confusing, if not poor, example and refrained from punishing him.

My father barbecued the best pork steaks. They were a staple of my childhood, along with fried bass and crappie, and Braunschweiger sandwiches with Miracle Whip, or fried bologna and mustard. And, of course, sweet tea. It’s little wonder my father was diagnosed with diabetes in his 70s, and surprising it wasn’t sooner. I went cold turkey on sweet tea the week he told me that, but I do miss it.

Another favorite: pizza and McDonald’s fries. We’d order pizza from the bowling alley, this was before Pacific had its own Pizza Hut, and stop by McDonald’s for fries to go with. I’m pretty sure the pot had something to do with this.

He tapered off the pot smoking sometime in the early 90s, I think. The last time I remember him smoking dope, I still lived at home. He had his bucket of Oreos. I just got home from work, and I had turned on Pink Floyd’s Delicate Sound of Thunder. We watched it together, and (unusually for him) he was effusive (for him) with praise for it. The last time we were together, while I drove him to a medical appointment, I played it on the car stereo. If he recognized it, he gave no sign. But he said he liked it.

He finally gave up cigarettes in the mid-2000s, along with Tina. I don’t think he ever really missed tobacco, but he’d have been pleased if I smuggled in a bong the last time I went to visit him. Sorry, dad.

I think he was happy with Tina. If he wasn’t, he never complained to me. Outwardly he seemed happier, content with his life. Since they met so long after I was out of the house, I didn’t get to know Tina as well as I’d have liked, but I thought she was good to my brothers and good to my father. What more could you ask?

People talk about divorce like it’s the worst thing in the world, but there are only two ways marriages end — death, or divorce. His marriage to Tina ended when she passed away last July, having spent her final years tending to my father. Many years his junior, Tina’s death came as a complete shock to our family. Except my father, who wasn’t told. He would not have retained the information, some days he wouldn’t have even remembered her. When he would recall Tina, we’d simply say “she’s not here right now.”

There’s a lot to say about dementia and decline, but I think I’ll save that for another day. What’s relevant now is that I didn’t lose my father all at once on January 21st. I’ve been losing him for years. Bit by bit, he sort of disappeared.

He is gone now. Entirely. It doesn’t feel real, yet. I grab at it, manage to catch a glimmer of it out of the corner of my eye. Things he’ll never do again or do at all, things we’ll never talk about, things I will never know about him or his life. The anchor that holds me in place is that he’s not suffering anymore, not confused or scared, nor in pain. No more indignities.

It took me a lifetime to know my father to the extent that I do, and that was a flawed and incomplete understanding. I can’t really do him justice in a few thousand words. Before he was ravaged by dementia, he was a loud, funny, brash person who cared about fairness and kindness in his own way. He was my father, and I loved him.

Just read you story about your father. I had the pleasure of working with Ron at the Manchester Fire Dist. back in the old days. He was certainly a fantastic artist, I was just cleaning out some old stuff I had stored in the basement and can across a painting he had done for me on an old piece of barn wood. He did all the gold leaf lettering on the fire trucks and ambulances. He was a good firefighter and I can’t recall why he quit the fire service, I guess it was to follow his dream of painting.

I was saddened to learn of his struggles and of his passing. RIP Ron.